How can students’ creativity be cultivated in education?

Review

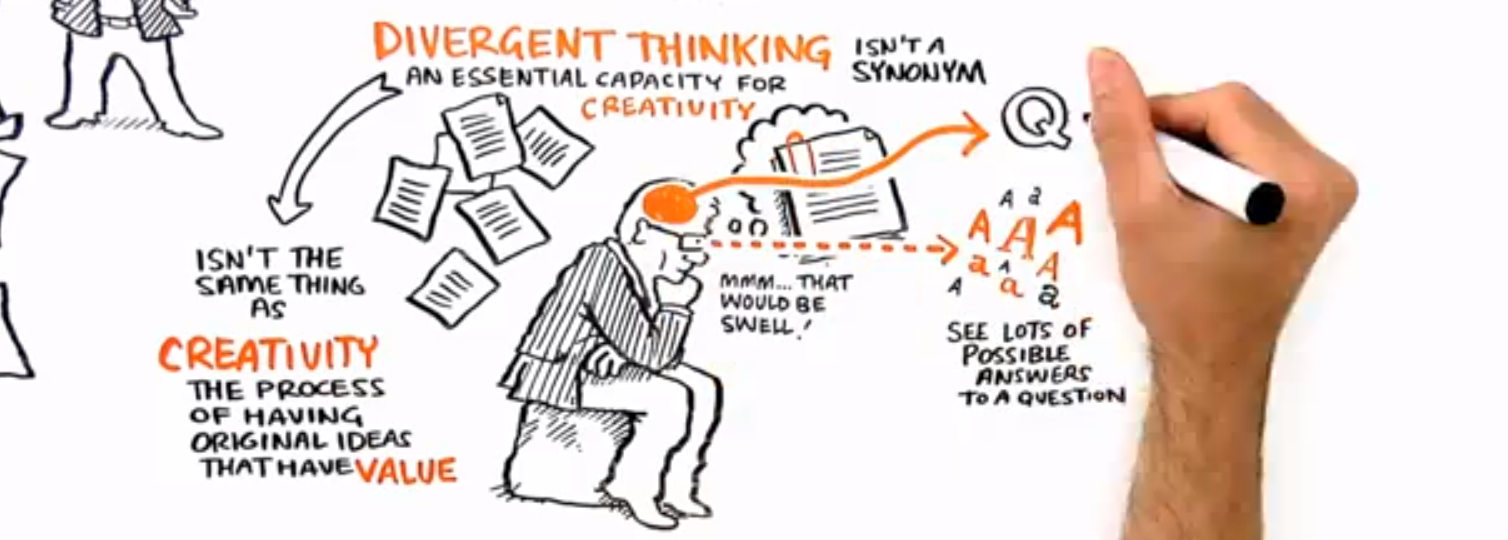

© RSA Animate Series

Introduction

The wonderfully animated video of Sir Ken Robinson’s Changing Education Paradigms (RSA Animate, 2010) has been viewed over 15 million times, so its message clearly resonates with many people. I must admit I was mesmerised too the first time I watched it. In this talk Robinson explains how our whole educational system is modeled on the interests of industrialism and no longer suitable in this day and age, with its endless possibilities and its information overload. Education thus alienates children from school and it kills their creativity. Robinson’s incessant crusade for creativity (Robinson & Aronica, 2016) may start to sound like a worn out recording, but he sure gathers a following.

Nevertheless, creativity is considered to be one of the most important 21st century skills, not only in the business world as an important element of economic prosperity (Craft, 2003) but also for students (Adams Becker et al., 2017; Wyse & Ferrari, 2015). In a world where collaboration and knowledge creation are buzz words, these skills play an increasingly important role (Muukkonen & Lakkala, 2009). This applies to all levels of education. According to Livingston (2010) “Higher education needs to use its natural resources in ways that develop content knowledge and skills in a culture infused at new levels by investigation, cooperation, connection, integration, and synthesis. Creativity is necessary to accomplish this goal”. However, it is virtually impossible to develop these metaskills other than within a specific domain (Baer, 2016).

The place of creativity in the national curricula of European nation states may vary, but they all value the relevance of creativity in education. Well … do they all? On page 36 of Wyse and Ferrari (2015) a shocking fact can be found: In a visual about the place creativity has in the EU curricula The Netherlands are dangling at the very bottom of the list (together with Poland). So clearly there is work to be done, and this international symposium, hosted by The Radboud Teachers Academy is one way of making educators aware of the importance of creativity. The purpose of this day is to connect, share and learn about creativity teaching with peers across disciplines, starting from the central question ‘How can students’ creativity be cultivated in (secondary) education?’. The teaching of creativity is central to the Research Programme of Radboud Teachers Academy.

30My research into this subject resulted in two questions that I would like to have answered:

- Which role can teachers play in the cultivation of students’ creativity?

- How can you apply a general concept as creativity to a specific domain?

Welcome and programme

Prof. Pauline Meijer (Radboud University, Teachers Academy) opens the conference with the observation that schools are slowly opening up to the notion and the necessity of creativity, and that they allow creative processes to be part of the curriculum. Doing research on creative thinking and creative processes is quite challenging, and today we will be exploring this together. A range of experts will shed some light on this topic.

Three years ago the Radboud University started a new research programme: Teaching for Creativity. It turned out that teachers needed an answer to this question the most: ‘How can you allow for more creativity in your classroom?’ So not only doing descriptive research, but also change things in classrooms. Meijer mentions as a casual remark that creativity doesn’t rule out knowledge and skills. But as stated in the introduction: Based on the research I’d say quite the contrary! Creativity cannot exist without knowledge and skills, because it needs context (Baer, 2016; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014; Livingston, 2010). One of the authors the research programme is built on is the keynote speaker today: Ronald Beghetto.

Keynote by Dr. Ronald Beghetto

Unfreezing Creativity: Toward a More Dynamic Approach to Understanding Creativity in Classrooms

Preamble: How might researchers move away from the typical, static approaches for conceptualizing and studying creativity in classrooms? Why might it be beneficial (and even necessary) to approach creative thought and action more dynamically? Two highly interesting questions. Beghetto does a lot of research in classrooms (Beghetto, 2013; Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014; Gajda, Beghetto, & Karwowski, 2017), so one would expect him to provide at least some tentative solutions.

Beghetto takes the floor energetically and convincingly, walking back-and-forth the isle. He starts with the introduction of a technique he often uses to unleash original thoughts: Prefacing your assumptions with ‘What if?’. In this way he looks to be disruptive. He promises to make this keynote interactive by using this technique in the last half hour or so with the audience.

What is creativity? According to Beghetto creativity is really “a distinction we bestow upon phenomena retrospectively”. In other words: it is not the phenomenon itself, but only after we’ve had an idea we label it as creative. What are the criteria by which we judge something to be creative or not? The first criterion would be that it involves originality or uniqueness. The second criterion would be that it has to be meaningful, useful or relevant, in other words ‘meeting the task constraints’. Here Beghetto refers very clearly to creativity needing the scaffold of a specific domain (Baer, 2016). These two criteria can be rendered by the following equations: C = O x TC (Creative = being Original within the Task Constraints), or Creative = [Original x Appropriate]context (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014).

To visualise the developmental trajectory of being creative Beghetto shows a graph with four stages: (1) Mini-C, which can grow with the help of feedback to (2) Little-C, wich needs disciplined preparation to grow to (3) Pro-C, and time can make it evolve into (4) Big-C (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014). So creativity thrives on feedback, disciplined preparation, and time. This sheds a different and interesting light on being creative, which is very often thought to be something that just pops up out of the blue when you are a creative person.

Beghetto spills meaningful oneliners profusely. “People always say you need to think outside the box: but no!! You need to think inside the box: work with the constraints. Or maybe break down the box and build a new one …”

In the classroom students may choose or need to be creative when there is insecurity and genuine doubt. That is the catalyst for creativity, because familiar ways of reasoning are no longer serving us. We could even induce this uncertainty by asking Wat if? questions. But as educators we are inclined to eliminate uncertainties (Beghetto calls this ‘Killing ideas softly’), because we fear curricular chaos. This makes teachers wary of creativity. Beghetto suggests we could every now and then grasp these moments of uncertainty and explore them, thus allowing for creativity to emerge.

Encouraging creativity can go hand-in-hand with classroom learning and it has to be seen as a basic curricular task, according to Pang (2015). His concept of ‘idea-generation tasks that you can use with any school subject’ is a very practical translation of Beghetto’s more philosophical and conceptual notions.

The last part of his keynote is an interactive exercise in ‘What if?’. The audience asks questions, which Beghetto is not going to answer, but which may lead to sparks of creativity. “What if the task constraints are so small it is impossible to be creative? What if the outcomes destroy the box but are not recognized as such? What if everyone is original and thus nobody is original any longer? What if a teacher is not able to create an environment that is inducive to creativity?” The audience loosens up and Beghetto takes it to the next level: The microphone goes round and the audience can “take a beautiful risk” and share assumptions about what is not really working for them professionally. The other participants ask ‘What if?’ questions and thus spark a bit of ‘Little C’. The start is hesitant, but eventually some participants share their professional issues with creativity. The ‘What if’s’ are flying about.

Beghetto wraps the keynote up with a nice paradox: “We do need some sort of structure to experience uncertainty and work with it in a productive way”.

Expert pitches

- The domesticated imagination

Pieter Fannes (University of Leuven)

Preamble: The topic creativity is viewed from an unusual angle in this pitch: anxiety – about the decline of creativity, but also, more surprisingly, about the imagination itself. Fannes argues that ‘the emergence of creativity as an educational goal is inextricably linked to these fears. The history of creativity should be understood as a process of “domestication” rather than as one of “liberation”’. I am curious to learn why the ‘beast of creativity’ had to be domesticated and what we can do to liberate it.

Fannes argues that until the late 20th century mankind has always been afraid of creativity and tried to stifle it. It had to be domesticated by rules and regulations. However, a wind of change is blowing, and creativity is seen as a flywheel for innovation these days. He refers to Robinson’s plea for creativity: The world is moving towards a catastrophe and we need creativity to find solutions. But this creativity is stifled by education (Robinson & Aronica, 2016). Fannes questions this assumption: “It is strange that creativity is the only mental capacity that can be killed by education. Nobody claims that the capacity for love and happiness is stifled by school, even though schools can be quite loveless places.” Other assumptions from those days were that creativity is fragile, and two-sided (destruction being the other side of the coin). So maybe this fear of creativity isn’t entirely without justification, and it may be good to question the necessity for endless creativity (Craft, 2003). It definitely has a flipside. As Fannes puts it: “Why are we bad for the planet? Because we are creative.” So think twice before you liberate the beast of creativity!

- Creativity and executive functions: Friends or enemies?

Evelyn Kroesbergen (Radboud University Nijmegen)

Preamble: Executive functions, including focused attention and goal-directed behaviour, have been found to be good predictors of academic abilities. However, the smartest children often show high levels of creativity, which requires distributed attention and divergent thinking. This raises the question how creativity and executive functions interact during academic tasks. Again an interesting angle and relevant for my own practice as well. Academic learning often requires lots of focused attention, so it will be enlightening to see how distributed attention and goal-directed behaviour relate to each other.

Kroesbergen states that chaos and order are both necessary for creativity. Well, here is an emerging pattern: think of Beghetto’s last observation: “We do need some sort of structure to experience uncertainty and work with it in a productive way”. However, it depends on the context or constraints, which of the two children show: focused attention (order) or distributed attention (chaos). Research has shown that creative children are better able to regulate the functioning of their cognitive control system in interaction with the context (Zabelina & Robinson, 2010).

Mathematics is Kroesbergen’s field of expertise, and naturally the executive functions play a big role in this domain. But there is more than just executive functions; we should also focus on distributive attention. Situated creativity (to act upon the importances of the environment) is crucial according to Kroesbergen, because being distracted by your invironment can lead to new ideas. During distractions there are processes in the brain that may lead to unexpected solutions. That is why we have to allow children to be distracted in the classroom sometimes. Differentiation in teaching strategies can be helpful to allow your pupils to show both focused and distributed attention, so it is time to recognise that convergent and focused thinking should not always be the goal in teaching. A striking view for a math professor.

- The history of creativity in education as a history of the present: Not all that glitters is gold

Bart Vranckx (University of Leuven)

Preamble: Very few concepts have gotten such a positive press as creativity. It is mostly seen as a given; a timeless, universal and “natural” concept. By looking at the conditions that made it possible for creativity to arise as an independent educational concept, this view will be problematized and historicized through a genealogical approach (Foucault). At first glance, this pitch has little to do with my own interests and professional practice, but I may just be surprised by its content.

Fannes explained in his pitch that the construct of creativity as we know it has originated in the 19th century. Vranckx takes it from there and summarizes the findings of his research (Vranckx, 2014) in a meandering and abstract monologue. He distinguishes three important periods in the recent history of creativity. In the seventies it was considered to be some sort of holy grail and a panacee for everything (“Creativity will help humanity out of the blind alley our world has become”). The eighties marked a period of disappointment: apparantly not everything could be solved by being creative. The construct was reintroduced in the nineties as part of the competencies-based approach to education. This meant a change from a ‘social self’ to a neo-liberal ‘entrepreneurial self’. Creativity is used as an economic commodity rather than a tool for self-development. This connection of creativity and entrepreneurship has become commonplace both in business and in education and even concepts like learning outcomes are interpreted in economic terms (‘leerwinst’). Schools have to provide their students with the tools to use in a competitive society, and creativity is one of them.

- From product to process: Documenting the messiness of creative work in schools and classrooms

Ronald Beghetto (Universtity of Connecticut)

Preamble: This brief pitch will highlight the importance of revealing the behind-the-scenes messiness of creative endeavors. An argument will be made for helping young people become better acquainted with the to-be-determined process in their own and other’s creative endeavors. I expect to have a peek at Beghetto’s practice and in all probability it will be a follow-up to the keynote.

Beghetto elaborates on a project he has been working on recently. Students are presented with real-world, complex problems, and tackle them together. He calls this ‘Legacy Projects’ (Beghetto, in press). Examine why something is a problem and what you can do to address it, and thus create ‘a lasting legacy’. Students document their process in reflective journals, artefacts et cetera, rather than focusing on the outcome. Whether it is a colossal failure or a success does not matter: students present on the ‘behind the scenes experience’ and thus tell their story about creative endeavours. You can label it as ‘the biography of an idea’.

This resonates with me, since I teach a creative subject at the University of Applied Sciences where students research their inspiration sources for a few weeks and present the outcomes in an ‘Inspiration Book’ (Overdiep, 2017). They keep a very detailed process journal throughout the module, and it is considered to be as important as the final product. Students don’t particularly like documenting their process, but in this pitch Beghetto points out the importance. “What if, rather than focusing on the deliverable, we embraced the mess of the process, and what we can learn from it?” Legacy projects offer one way for educators to help cultivate the capacity to successfully address complex and often ill-defined challenges (Beghetto, in press).

Workshop 1: How starting to teach for creativity relates to teacher learning

Prof. Paulien Meijer (Radboud Teachers Academy)

Preamble: When beginning or experienced teachers decide to open up their classrooms for creative learning, they cannot suffice with merely applying creative assignments, according to Meijer. In a course on teaching for creativity, it appeared that (student) teachers ended up with working on personal goals such as developing courage, accepting and welcoming uncertainty. So interestingly enough, there is a connection with Fannes’ pitch about creativity and anxiety. It is almost as if creativity is something to be afraid of… I would love to learn more about what type of learning teachers need so they will be brave enough to teach for creativity.

The Radboud Teachers Academy developed a one year postacademic programme for university student teachers who aim to teach in upper secondary education. Part of this programme is a course Teaching for Creativity, which is based on ‘Teach as you preach’. So there is a lot of emphasis on creative exercises, experimentation, and stimulation to express and elaborate on genuine ideas and feelings. The guiding principle of this course comprises the following three questions: What does creativity and the cultivation of it mean for (1) my pupils, and for my subject area, (2) me as a person and as a teacher, and (3) my professional context (colleagues, school, et cetera). The pilot yielded some surprising insights. At first students focused on their pupils’ creativity, but almost immediately a strange phenomenon occurred: students appeared to be deeply uncertain about their own creativity and were reluctant to let go of predictability and certainty. This obviously hinders the creative process; think of Beghetto, who has shown us that the basis of all creative endeavours is uncertainty.

What we learn from this workshop is you have to examine your own attitude towards uncertainty first before you can teach others to be creative. A very valuable lesson indeed!

Intermezzo: What will it be?

A conference about creativity cannot all be about theory and critical thinking, so in the intermezzo the participants engage in some lateral thinking and acting. The assignment is as follows: develop a logo and the accompanying slogan for the conference Teaching for Creativity. Every group has 25 minutes to come up with a creative solution. The process in our group was definitely messy, but we were quite content with the result: a 3D rendering of the conference (with twisted paperchain).

Workshop 2: ‘Finally, something different.’ Creative writing in upper secondary education

Drs. Anouk ten Peze (University of Amsterdam)

Preamble: In this workshop, the ingredients of an effective creative writing instruction will be discussed and the assessment of creative texts will be explored. At the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences I developed several modules Professional writing and I hope go get some pointers as to how one can integrate creative writing techniques in such modules. This will improve students’ writing skills and teach them to adopt a more playful and creative approach.

Creative writing is no longer part of the curriculum in Dutch secondary schools. Students are seldom required to write fictional or expressive texts, but instead only functional writing is being taught (e.g. essay writing, argumentation). Ten Peze conducts research on the effect of creative writing on students’ writing processes and text quality, and in this workshop she shares the highlights with us. Since the data analysis is still in progress, she can only provide tentative outcomes. The research will be used to develop a module creative writing for upper secondary education (havo/vwo).

In the study Peze examined whether adolescent students distribute subprocesses of their writing process (e.g., planning, formulating, revising) differently when writing creative texts compared to expository texts. The Consensual Assessment Technique was used to determine the creative quality of a text (Amabile, 1982). The participants get to experience this technique, in which an expert assesses two texts and decides which one is the more creative. This proves to be quite challenging in a group: our group of three ‘experts’ gets caught up in a debate about what creativity in writing actually is …

The tentative outcome of Peze’s research suggests that differences in the quality of the creative stories are a result of the different ways students organize the subprocesses of the creative writing process.

Plenary final

The party gathers on the 26th floor (splendid view!) for a wrap up. Throughout the day participants had to assemble their insights in three categories: (1) This is a new insight, and eye opener for me, (2) This is my (new) question, and (3) This is how I would like to continue to work on my questions. Some of the more striking findings are elaborated upon and I even get my one minute of fame, clarifying my personal eye opener. I never realised there were two sides to creativity. The construct is always considered to be positive and useful, but there is also a destructive side to creativity (Fannes’ “Why are we bad for the planet? Because we are creative.”) The eye opener of a fellow participant links up with this perfectly: “We need creativity to survive the effects of creativity”. Many of the questions concern the translation of these insights to the classroom. What we want to explore further is ‘How can we help teachers to recognize those instances when there is an opportunity to nurture and develop creativity?’ We are all determined to use creativity more deliberately to improve teaching and education. On this positive note the conference draws to a close and everybody rushes to the bar for drinks, tapas and animated conversation about teaching for creativity and many other topics.

Evaluation

‘How can students’ creativity be cultivated in (secondary) education?’ was the central question of this symposium and its purpose was to connect, share and learn about creativity teaching with peers across disciplines. My personal questions (1) Which role can teachers play in the cultivation of students’ creativity? and (2) How can you apply a general concept as creativity to a specific domain? have not been answered in the form of a blueprint that I can use whichever way, but rather like the metaphorical seed that has been firmly planted in my brain. And I have gained two insights: (1) the beast of creativity (it has two sides and this is why throughout the ages people have also been afraid of it), and (2) Beghetto’s practical and gentle approach to creativity. Creativity needs time and thrives on feedback.

The scientific net weight of this conference is lower than the previous one I attended (partly because the afternoon was devoted to workshops), but I picked up quite a few practical applications, and the accompanying literature provided an extra layer of comprehension. The small-scale set-up made it possible to interact with many participants and (keynote) speakers during breaks and lunch. Our small party of OU students had an informal lunch with the two Belgian scientists Fannes and Vranckx, and enjoyed a private lecture about dr. Fröbel.

Beghetto’s keynote was very interactive. He is a seasoned keynote speaker and this shows. He takes his audience on a journey with a clear purpose. His Legacy Approach is something I will be returning to in my own practice. This is so far removed from the superficial way creativity is often approached: classrooms full of students, engaging in generic mindmapping and brainstorming that have little to do with the subject matter of the classroom is not what creativity is about (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2014; Byron, 2012). The expert pitches were short, intensive and quite theoretical. I found myself drifting at times during the first three pitches, and this may have to do with the fact that the language of communication was English. The difference between the eloquency and fluency of Beghetto and the somewhat hesitant presentation of most other speakers must partly be blamed on this. The workshops were not really workshops, but rather lectures with some interactivity in the form of questions. However, they had a practical approach and part of the theory of the morning sessions ‘landed’ here. All in all, it was an inspiring day with a strong theoretical web woven from Beghetto’s research: the same constructs were elucidated from different perspectives.

In fact, I can sum up the fruit of this conference in a creative oneliner: The beast of creativity: there is no need to domesticate or liberate it. Just gently guide it from little-C cub to well-muscled and lithe Big-C tiger, using feedback, deliberate practice, and time!

Literatuur

Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Davis, A., Freeman, A., Hall Giesinger, C., & Ananthanarayanan, V. (2017). NMC Horizon Report: 2017 Higher Education Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Amabile, T. M. (1982). The Social Psychology of Creativity: A Consensual Assessment Technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(5), 997–1013.

Baer, J. (2016). Creativity Doesn’t Develop in a Vacuum. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2016(151), 9-20. doi:10.1002/cad.20151

Beghetto, R. A. (2013). Killing ideas softly? The promise and perils of creativity in the classroom. Charlotte, NC, US: IAP Information Age Publishing.

Beghetto, R. A. (in press). Legacy Projects: Helping Young People Respond Productively to the Challenges of a Changing World. Roeper Review, 39, 1-4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2017.1318998

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies, 25(1), 53-69. doi:10.1080/13598139.2014.905247

Byron, K. (2012). Creative Reflections on Brainstorming. London Review of Education, 10(2), 201-213.

Craft, A. (2003). The Limits To Creativity In Education: Dilemmas For The Educator. British Journal of Educational Studies, 51(2), 113-127. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00229

Gajda, A., Beghetto, R. A., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Exploring creative learning in the classroom: A multi-method approach. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 24(1), 250-267.

Livingston, L. (2010). Teaching Creativity in Higher Education. Arts Education Policy Review, 111(2), 59-62.

Muukkonen, H., & Lakkala, M. (2009). Exploring Metaskills of Knowledge-Creating Inquiry in Higher Education. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(2), 187-211.

Overdiep, J. A. (2017). Inspiration Book: Manual. Amsterdam Fasion Institute (AMFI). Amsterdam.

Pang, W. (2015). Promoting creativity in the classroom: A generative view. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(2), 122-127. doi:10.1037/aca0000009

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2016). Creative Schools: Revolutionizing Education from the Ground Up. New York: Viking.

RSA Animate. (2010, 14 October). Changing Education Pargadigms. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U

Vranckx, B. (2014). Creativity as a History of the Present in Belgian Education: From ‘New and Appropriate” to “Entrepreneurship” (1950-2013). Knowledge Cultures, 2(3), 74-97.

Wyse, D., & Ferrari, A. (2015). Creativity and Education: Comparing the National Curricula of the States of the European Union and the United Kingdom. British Educational Research Journal, 41(1), 30-47.

Zabelina, D. L., & Robinson, M. D. (2010). Creativity as flexible cognitive control. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(3), 136-143. doi:10.1037/a0017379